Cultured Story #15 Halston’s Manhattan Townhouse

An Urban Monument to Modernism

Tucked away on Manhattan’s Upper East Side—a neighborhood more closely associated with prewar townhouses and Beaux-Arts façades—stands a sculptural anomaly: Halston’s House. Located at 101 East 63rd Street, the residence is a commanding testament to the architectural daring of Paul Rudolph, one of America’s most original and misunderstood modernists. Completed in 1968, the house introduced stark modernism into one of the city’s most conservative zip codes.

This four-story townhouse, composed of poured concrete, glass brick, and steel, reimagined the concept of domestic living. Its exterior appears fortress-like and mysterious—Brutalist in its massing but softened by translucent glass bricks and Rudolph’s use of cantilevered geometry. Even the entrance is subtly tucked away, heightening the sense that the visitor is entering a private, almost cinematic world.

If you aren’t subscribed yet, hit the subscribe button below to receive the Cultured Stories every week, directly in your inbox

The Vision of Paul Rudolph

Commissioned by real estate attorney Alexander Hirsch and his partner Lewis Turner, the house offered Rudolph—then the chair of the Yale School of Architecture—an opportunity for complete artistic control. Already celebrated for his expressive, layered forms and daring use of industrial materials, Rudolph approached the townhouse not as a series of rooms, but as a three-dimensional spatial journey.

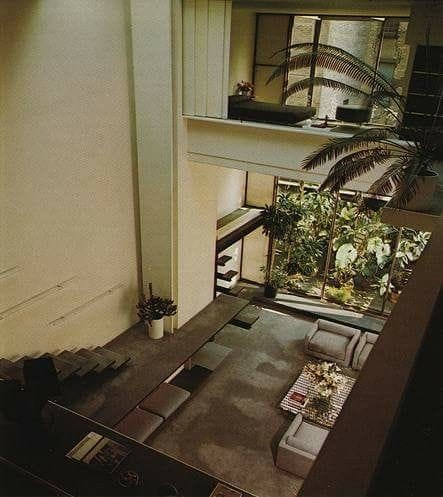

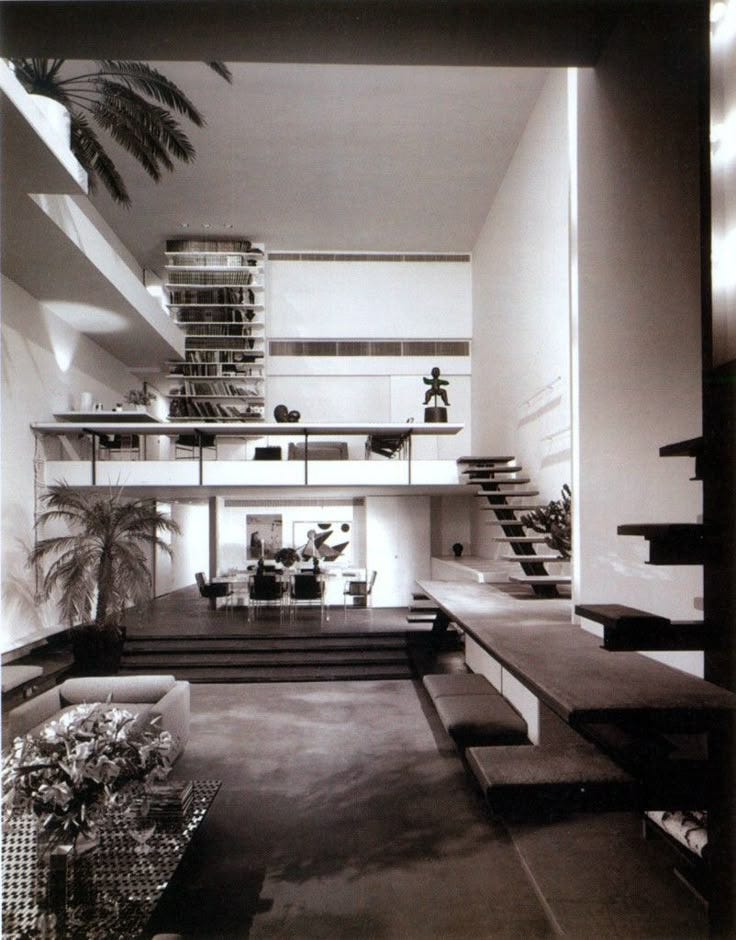

He designed the residence as a vertical labyrinth of interlocking platforms, mezzanines, and bridges—what he called “spatial layering.” The floating staircases and split-level floors shift and unfold as one moves through the house, constantly revealing new angles and perspectives. The design defied the linear, boxed-in layouts of traditional townhomes. Instead, Rudolph created an environment in which form followed emotion, not function.

No detail was left to chance: lighting, built-in seating, metallic walls, and acoustics were all choreographed to enhance spatial drama. Polished aluminum and smoked mirrors bounced light across concrete surfaces, making the space feel both grounded and ephemeral. It was not so much a home as a living, breathing architectural installation.

Halston Arrives: Fashion Meets Architecture

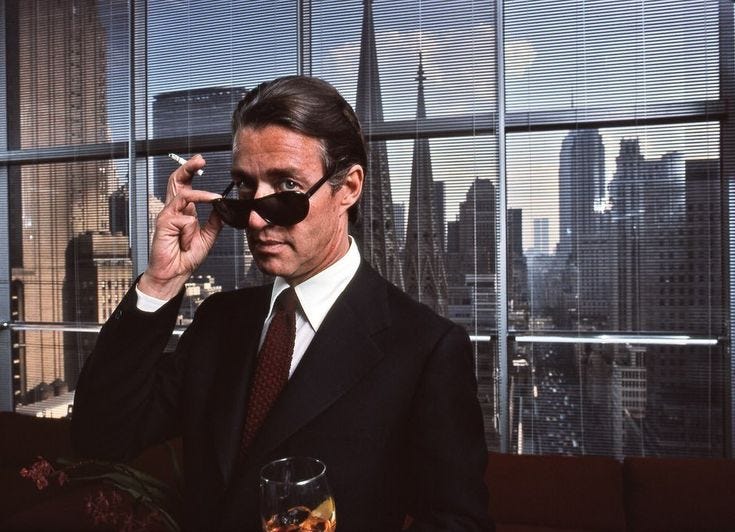

In 1974, the house was purchased by Roy Halston Frowick—known simply as Halston—America’s reigning fashion designer at the time. Halston was drawn to the house’s bold geometry and minimalism, which reflected his own design sensibility. Just as Rudolph manipulated space through architectural restraint, Halston revolutionized American fashion with clean lines, luxe materials, and fluid simplicity.

Halston’s occupancy would transform the house from an architectural curiosity into a full-fledged cultural landmark. It became a salon for the glittering personalities of 1970s New York:

Liza Minnelli

Andy Warhol

Elizabeth Taylor

Bianca Jagger

Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager (of Studio 54 fame)

Elsa Peretti (jewelry designer and Halston muse)

Yves Saint Laurent

The living room, with its soaring ceilings and soft white carpet, played host to fittings, dinners, and private conversations. Halston worked closely with decorator Paul Fortune and lighting designer Joe D’Urso to refine the interiors, leaning into his signature palette of ivory, silver, and gray. Furniture was kept low and modular, upholstered in suede or lacquered finishes. The space was theatrical, but never fussy—curated for conversation, elegance, and ease.

A Study in Light and Movement

The true heart of the house was its central living area: a double-height volume flooded with light from floor-to-ceiling glass brick walls. The effect was almost ecclesiastical. In this space, architecture, fashion, and art converged. Warhol portraits leaned against mirrored panels. Music echoed across hard surfaces. Time slowed.

Rudolph’s dynamic use of natural and artificial light became part of the home’s choreography. Narrow beams illuminated stair treads, while reflective materials amplified the ever-changing interplay between sunlight and shadow. Light danced across surfaces and bounced through gaps, altering the atmosphere from hour to hour.

Even the absence of color was deliberate. The pale palette allowed textures—metal, stone, leather—to take precedence. The rooms didn’t impose themselves; they revealed themselves.

Private Retreats Within the Vertical Choreography

Though dramatic in volume, the house was also deeply personal. Rudolph designed the layout to allow for openness and seclusion to coexist. There were no hallways; rather, platforms and mezzanines flowed into one another, allowing movement to feel organic and unforced.

The private quarters—including bedrooms and dressing areas—were serene and spare. The master suite featured large windows that framed abstract views of the city, while the furnishings remained minimal: a bed, a chair, a small writing desk. The materials—suede, polished wood, matte stone—invited touch and softened the edges of the space.

Halston, ever the perfectionist, added custom storage for his vast collection of cashmere, silks, and caftans. Yet the rooms never felt crowded or ostentatious. They whispered instead of shouted.

The Rooftop Garden: A Living Extension

Among the most striking features of the home was its rooftop garden—a rarity in 1960s Manhattan townhomes. For Halston, this was a private sanctuary high above the city’s chaos. Enclosed and landscaped with sculptural greenery, it offered a moment of softness and silence atop a monument of steel and stone.

Here, twilight cocktail hours blurred into after-hours conversations under the stars. The garden’s elevation and enclosure created a sense of intimacy, even as the skyline shimmered beyond. Though the original design did not include a pool, Rudolph’s sensitivity to natural elements made the space feel fluid and meditative, in keeping with his use of water in other projects like the Milam Residence and Yale Art & Architecture Building.

An Enduring Legacy

Over the years, Halston’s House has become mythologized—not just for its celebrity pedigree, but for its fearless architectural ambition. It is one of the few private residences by Paul Rudolph that survives largely intact, making it an object of study and admiration among architects and preservationists.

For decades, it has inspired a new generation of designers drawn to its unapologetic minimalism, its manipulation of space and light, and its defiance of traditional domestic norms.

It reminds us that Mid-Century Modernism was never just a style—it was a radical reimagining of how we live. And in a time of algorithmic design and visual overload, Halston’s House remains tactile, intentional, and human. It asks us to move more slowly, observe more closely, and live more consciously.

The House as Mirror

In many ways, the house is a reflection of its most famous occupant. Just as Halston cut his garments to accentuate movement and mood, Rudolph sculpted space to heighten awareness and emotion. Both men worked in the language of restraint. Both believed in the sensual power of simplicity.

Together, they transformed 101 East 63rd Street into something greater than a residence. It became a collaboration across disciplines—a visual dialogue between architecture and fashion, volume and silhouette, structure and style.

Best Books About Halston:

Simply Halston The Untold Story

William Morrow & Co The Last Party: Studio 54, Disco, and the Culture of the Night

The Beautiful Fall: Lagerfeld, Saint Laurent, and Glorious Excess in 1970s Paris

— Faith

Do you know anyone who would love to read this Cultured Story? Show your support by sharing the Cultured Elegance Newsletter and earn rewards for your referrals.